The domestication of frozen water

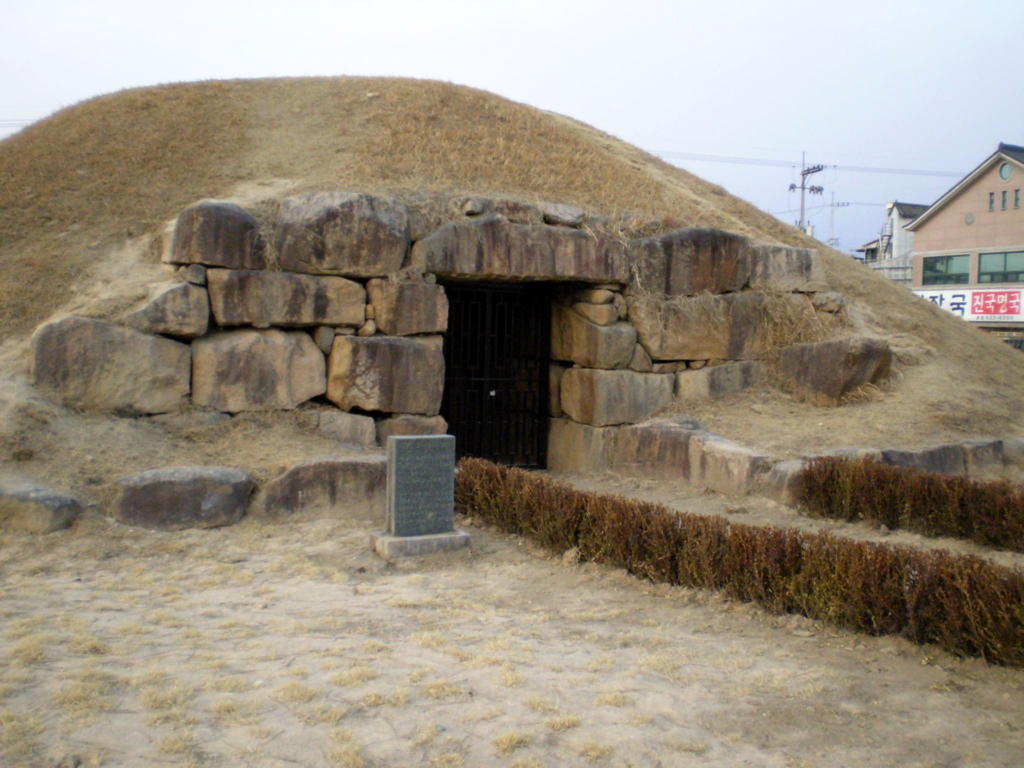

An ice house in South Korea.

If there is any one modern innovation that would be both perfectly understandable to the medieval visitor yet completely amazing in spite of it, it is the ubiquity of ice.

Sure, matches are cool, but they’re really just fancy tinder kits. And the educated among our medieval ancestors would certainly know of the wonders of Rome’s waterways. But ice? Ice has never served man so well as it does today.

My grandfather worked, as a teenager, in an icehouse. He hated it. Ice blocks had to be big, or they’d melt. Water is heavy enough in small quantities; carrying those ice blocks to people’s trucks was a very strenuous task.

From there people could purchase it for their own iceboxes (the immediate predecessor to the refrigerator) or their own insulated or basement ice house. Or they could buy it when they needed it for a party and use it until it melted. But it was cheap only compared to what it cost before the advent of ice houses, which is to say, compared to a near impossibility.

The ice “factory” my grandfather worked at didn’t create the ice: it kept ice from the winter when the lake froze over. Ice from the lake was cut into blocks and stored in a warehouse, then covered in insulators such as straw and sawdust to keep the heat out. The blocks were big enough that, properly insulated, they could keep for months, long enough to last through the summer until the lake froze again.

This also meant that ice could be transported in ships to climates that had no winter.

Storing ice became popular only when it became easy to cut ice, transport it, and keep it stored in bulk through the summer. A relatively wealthy market was also necessary for icehouses to become viable. Persia did it, when Persia was the center of civilization, and it was common enough in the United States as average wealth began to rise. But even then, ice was bulky and difficult to work with, and required year-long planning.

Simply popping water into a kitchen storage unit and waiting an hour? Incredible! The stuff is so cheap now we even toss it in chunks to kids to keep them quiet and amused. Ice is so cheap that soda—itself so cheap that it usually comes with free unlimited refills—is always cut with ice in restaurants. Think about that: this thing that was usually impossible at any price is now filler in sugared water.

Ice is everywhere today. Many modern refrigerators come with icemakers built in, but if not you can pop some water in a tray, put it in your freezer and have ice readily available in an hour.

If you have an abundance of water, you can make a limited refrigerator pretty easily. Evaporative cooling works on the simple principle that when water evaporates, it takes energy to do so. As long as the evaporated water leaves the area before it re-condenses, the area around the evaporation will be cooled.

How to cool off on a hot day…

You can build an evaporative refrigerator using sand, water, cloth, and two containers, one small enough to fit inside the other and with room to spare for the sand and water.

- Place the sand in the larger pot, and soak it with water.

- Place the smaller pot in the larger pot, so that it is surrounded with wet sand.

- Place the food in the smaller pot.

- Place a wet cloth over the top of the pots.

- Keep the sand and the cloth wet as water evaporates from them.

Smaller pots are better. A breeze helps a lot, too, as it takes the evaporated water away before it can recondense and bring the temperature back up. And if you can raise the pots off the ground a bit, so that the breeze can blow under it as well, that will help, too—just like it does with bridges.

The lower the humidity and the higher the wind speed, the colder the pot will get.

However, evaporative refrigeration will not practically freeze its contents, and it requires dry air: in humid air, no evaporation occurs, and it’s the act of evaporation that causes evaporative cooling.

Bridges can freeze from evaporative cooling, but usually only do so in near freezing temperatures anyway. With extremely high wind, bridges can freeze further and further from 32 degrees.1

Persia made use of this to create ice in giant evaporative coolers, but it worked the same way bridges do: in winter, when the temperature was dropping to freezing anyway, the evaporative process helped them create ice faster. The process was likely helped by the fairly low humidity in the Persian desert—and also by the simple method of running the water in the more shaded north side of the structure.

Evaporative cooling can also be used as simple air conditioning, but it requires a breeze, either natural or man-made, to take the evaporated water out of the area that needs to be cooled.

Without reliable cooling, you need to take steps to preserve anything that could spoil—you need to salt and dry meats, turn your fruit juice into alcohol, keep your buildings well-ventilated. You will can, dry, or pickle as many fruits and vegetables as you can to save them for later consumption or for trade. You will eat a whole lot of grains and beans, because dried grains and dried beans last a long, long time.

And what you can’t preserve, you will consume immediately, in some big blow-out event for your family, your extended family, or your community. Without refrigeration you can, in fact, run regularly from feast to famine, on a yearly or seasonal cycle.

Most likely high technology or magic spells could be created to provide the appropriate conditions for evaporative freezing, but they could also be used to produce non-evaporative freezing.

↑

cooling

- Build an evaporative refrigerator

- “Food is stored in the inner pot which can be covered by a wet towel or a lid. As the water evaporates from the sand, it cools the inner pot and its contents.”

- Pot-in-pot refrigerator at Wikipedia

- “There is some evidence that evaporative cooling was used as early as the Old Kingdom of Egypt, around 2500 B.C. Frescos show slaves fanning water jars, which would increase air flow around the porous jars and aid evaporation, cooling the contents. These jars exist even today and are called “zeer”, hence the name of the pot cooler. Many earthenware pots were discovered in Indus Valley Civilization around 3000 BC which were probably used for storing as well as cooling water similar to present-day ghara or matki used in India and Pakistan.”

- Yakhchal at Wikipedia

- “Yakhchal is an ancient type of evaporative cooler. Above ground, the structure had a domed shape, but had a subterranean storage space; it was often used to store ice, but sometimes was used to store food as well. The subterranean space coupled with the thick heat-resistant construction material insulated the storage space year round. These structures were mainly built and used in Persia. Many that were built hundreds of years ago remain standing.”

ice

- Harvest of the Cold Months: The Social History of Ice and Ices: Elizabeth David (paperback)

- “An awe-inspiring feat of detective scholarship, the literally marvellous story of how human beings came to ingest lumps of flavoured frozen matter for pleasure.”

- Ice Harvesting

- “Before the 1830’s, food was preserved through salting, spicing, pickling or smoking. Butchers slaughtered meat only for the day's trade, as preservation for longer periods was not practical. Dairy products and fresh fruits and vegetables subject to spoilage were sold in local markets since storage and shipping farm produce over any significant distance or time was not practical. Milk was often hauled to city markets at night when temperatures were cooler. Ale and beer making required cool temperatures, and its manufacture was limited to the cooler months.”

- Ice house at Wikipedia

- “A cuneiform tablet from c. 1780 BC records the construction of an icehouse in the northern Mesopotamian town of Terqa by Zimri-Lim, the King of Mari, “which never before had any king built.” In China, archaeologists have found remains of ice pits from the seventh century BC, and references suggest they were in use before 1100 BC. Alexander the Great around 300 BC stored snow in pits dug for that purpose. In Rome in the third century AD, snow was imported from the mountains, stored in straw-covered pits, and sold from snow shops. The ice formed in the bottom of the pits sold at a higher price than the snow on top.”

- Ice trade at Wikipedia

- “The ice trade, also known as the frozen water trade, was a 19th-century industry, centering on the east coast of the United States and Norway, involving the large-scale harvesting, transport and sale of natural ice for domestic consumption and commercial purposes. Ice was cut from the surface of ponds and streams, then stored in ice houses, before being sent on by ship, barge or railroad to its final destination around the world. Networks of ice wagons were typically used to distribute the product to the final domestic and smaller commercial customers. The ice trade revolutionized the U.S. meat, vegetable and fruit industries, enabled significant growth in the fishing industry, and encouraged the introduction of a range of new drinks and foods.”

More ice

- Revolution: Home Refrigeration

- Nasty, brutish, and short. Unreliable power is unreliable civilization. When advocates of unreliable energy say that Americans must learn to do without, they rarely say what we’re supposed to do without.

More Medieval Life

- Currency and economic policy in the middle ages

- Prices, credit, and currencies. If you know the system, you could make a mint!

- The well of life: the revolution of reliable water

- Water is practically a modern invention: we use it far more today than we did a hundred years ago and we trust it more than we did a hundred years ago. Today reliable water is ubiquitous, and we complain if a building doesn’t have running water.

- How to build a fire

- The best way to make a fire is to start with a fire.